Religion in the Philippines

|

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Demographics of the Philippines | ||

|

Life in the Philippines |

|---|

| Culture Cuisine Dance Demographics Economy Education Higher education Film Holidays Languages Literature Martial arts Music Politics Religion Sports Tourism Transport |

Religion in the Philippines are spiritual beliefs held by Philippine citizens. Religion holds a central place in the life of the majority of Filipinos, including Catholics, Jewish, Muslims, Buddhists, Protestants and animists. It is central not as an abstract belief system, but rather as a host are experiences, rituals, ceremonies, and adjurations that provide continuity in life, cohesion in the community and moral purpose for existence. Religious associations are part of the system of kinship ties, patron-client bonds and other linkages outside the nuclear family.[1]

Christianity and Islam have been superimposed on ancient traditions and acculturated. The unique religious blends that have resulted, when combined with the strong personal faith of Filipinos, have given rise to numerous and diverse revivalist movements. Generally characterized by antimodern bias, supernaturalism, and authoritarianism in the person of a charismatic messiah figure, these movements have attracted thousands of Filipinos, especially in areas like Mindanao, which have been subjected to extreme pressure of change over a short period of time. Many have been swept up in these movements, out of a renewed sense of fraternity and community. Like the highly visible examples of flagellation and reenacted crucifixion in the Philippines, these movements may seem to have little in common with organized Christianity or Islam. But in the intensely personalistic Philippine religious context, they have not been aberrations so much as extreme examples of how religion retains its central role in society.[1]

Contents |

Ancient indigenous beliefs

Animism, is the term used to describe the indigenous spiritual traditions practiced in the Philippines during pre-colonial times. Today, a handful of the indigenous tribes continue to practice it. The traditions are a collection of beliefs and cultural mores anchored more or less in the idea that the world is inhabited by spirits and supernatural entities, both good and bad, and that respect be accorded to them through nature worship. These spirits all around nature are known as "diwatas", showing cultural relationship with Hinduism (Devatas). Some worship specific deities, such as the Tagalog supreme deity, Bathala, and his children Adlaw, Mayari, and Tala, or the Visayan deity Kan-Laon; while others practice Ancestor worship (anitos). Variations of animistic practices occur in different ethnic groups. Magic, chants and prayers are often key features. Its practitioners were highly respected (and some feared) in the community, as they were healers, midwives (hilot), shamans, witches and warlocks (mangkukulam), priests/priestesses (babaylan/katalonan), tribal historians and wizened elders that provided the spiritual and traditional life of the community. In the Visayan regions, there is a belief in the existence of witchcraft or barang and mythical creatures such as the "aswang", "balay sa dwendi" and "Bakonawa", despite the existence of the Christian and Islamic faiths.

In general, the spiritual and economic leadership in many pre-colonial Filipino ethnic groups was provided by women, as opposed to the political and military leadership according to men. Spanish occupiers during the 16th century arrived in the Philippines noting about warrior priestesses leading tribal spiritual affairs. Many were condemned as pagan heretics. Although suppressed, these matriarchal tendencies run deep in Filipino society and can still be seen in the strong leadership roles modern Filipino women are assuming in business, politics, academia, the arts and in religious institutions.

Folk religion remains a deep source of comfort, belief and cultural pride among many Filipinos. Nominally animists constitute about one percent of the population. But animism's influence pervade daily life and practice of the colonial religions that took root in the Philippines. Elements of folk belief melded with Christian and Islamic practices to give a unique perspective on these religions.

Judaism

As of 2005, Filipino Jews number at the very most 500 people.[2] Other estimates range between 100 and 500 people (0.000001% and 0.000005% of the country's total population).

Today, Metro Manila boasts the largest Jewish community in the Philippines, which consists of roughly 40 families. The country's only synagogue, Beth Yaacov, is located in Makati, as a Chabad House of the Ashkenazi Haredim.[3] There are, of course, other Jews elsewhere in the country,[2] but these are obviously fewer and almost all transients,[4] either diplomats or business envoys, and their existence is almost totally unknown in mainstream society. There are a few Israelis in Manila recruiting caregivers for Israel and a few other executives. A number are converts to Judaism. There are few Jewish, Hasidic, Messianic and Kabbalah groups that exists in the Philippines. In the Metro Manila, the Kabbalah Centre [5] established its first Kabbalah Study Group, with a total of 50+ members, as is the Ang Ilaw Kabbalah Study Group, which follows Hasidic tradition (Breslover) [6] houses its chapter in Antipolo City, Rizal.

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith in the Philippines started in 1921 with the first Bahá'í first visiting the Philippines that year,[7] and by 1944 a Bahá'í Local Spiritual Assembly was established.[8] In the early 1960s, during a period of accelerated growth, the community grew from 200 in 1960 to 1000 by 1962 and 2000 by 1963. In 1964 the National Spiritual Assembly of the Bahá'ís of the Philippines was elected and by 1980 there were 64,000 Bahá'ís and 45 local assemblies.[9] The Bahá'ís have been active in multi/inter-faith developments. No recent numbers are available on the size of the community.

Buddhism

Buddhism in the Philippines is largely confined to the Filipino Chinese, Chinese, Japanese, Indian, Korean, Thai, and Vietnamese communities. There are temples in Manila, Davao, and Cebu, and other places. According to the Pew Research Center, the 2000 Philippine census found that 0.1% of the population is Buddhist.[10] Other sources claim different figures, however. The publication, An Information Guide — Buddhism, for example, claims that as of 2007 Buddhists formed 2% of the total population.[11] Several schools of Buddhism are present in the Philippines - Mahayana, Vajrayana, Theravada Buddhist temples as well as Lay Organizations are present in the Philippines as well as meditation centers and groups such as Soka Gakkai International [12]

Christianity

Christianity arrived in the Philippines with the landing of Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. In the late 16th century, soldiers and missionaries firmly planted the seeds of conversion when they officially claimed the archipelago for Spain and named it after their king. Missionary activity during the country's long colonial rule by Spain and the United States transformed the Philippines into the first and then one of the three (perhaps four, considering South Korea's growing Christian population) predominantly Christian nations in East Asia, with approximately 92% of the population belonging to the Christian faith, the other Christian nations being East Timor and Papua New Guinea.

Catholic Church

Roman Catholicism is the predominant religion and the largest Christian denomination, with estimates of 81-85% of the population belonging to this faith in the Philippines. The country has a significant Spanish Catholic tradition, and Spanish style Catholicism is highly embedded in the culture, which was acquired from priests or friars (prayle in Filipino). This is shown in traditions such as Misa de Gallo, Black Nazarene procession, Santo Niño and Aguinaldo procession, where large crowds gather, honouring their patron saint or saints. Processions and fiestas are conducted during feast days of the patron saints of various barrios or barangays. Roman Catholicism is also the de facto state religion in the Philippines.

Every year on November 1, Filipino families celebrate the Day of the Dead, on which they spend much of the day and evening visiting their ancestral graves, showing respect and honor to their departed relatives by feasting and offering prayers. On November 1 Filipino families celebrate All Saint's Day, where they honor the saints of the Catholic church. November 2 is All Soul's Day.

Christmas in the Philippines is a celebration spanning just more than the day itself. Christmas season starts in September. Many traditions and customs are associated with this grand feast, along with New Year. Holy Week is also an important time for the country's Catholics. To help spread the gospel, the Roman Catholic Church established the Catholic Media Network with its main TV station Tv Maria as a tool for evangelization. Other large Roman Catholic television channels like EWTN and Familyland are also available and watched in the Philippines.

Roman Catholic Charismatic Renewal and the Neocatechumenal Way

The El Shaddai movement is a large Catholic Charismatic Renewal led by 'Brother Mike Velarde'. Other groups include Couples for Christ, Ligaya Ng Panginoon, FAMILIA Community, etc.

The Neocatechumenal Way has a very large and rapidly expanding presence in the Philippines, especially in Luzon, Manila and the Visayan Islands, especially Panay. Nowadays there are more than seven hundred Neocatechumenal communities, the highest number in Asia and one of the highest numbers in the World.

Orthodox Church

Orthodoxy has been continuously present in the Philippines for more than 200 years.[13] Today, Orthodox number at around 560.[14]

Protestantism and Evangelicals

Protestantism arrived in the Philippines with the coming of the Americans at the turn of the 20th century. In 1898, Spain lost the Philippines to the United States. After a bitter fight for independence against its new occupiers, Filipinos surrendered and were again colonized. The arrival of Protestant American missionaries soon followed.

- Association of Fundamental Baptist Churches in the Philippines

- Baptist Bible Fellowship in the Philippines (Baptist)

- Philippine General Council of the Assemblies of God

- Christian and Missionary Alliance Churches of the Philippines

- Church of the Foursquare Gospel in the Philippines (Pentecostal)

- Church of the Nazarene (Holiness)

- Conservative Baptist Association of the Philippines (Baptist)

- Convention of Philippine Baptist Churches (Baptist)

- Episcopal Church in the Philippines (Anglican)

- Every Nation Churches and Ministries (Pentecostal)

- Jesus Is Lord Church (Pentecostal)

- Church of God (Cleveland)

- Luzon Convention of Southern Baptists (Baptist)

- Mindanao and Visayas Convention of Southern Baptists (Baptist)

- Lutheran Church in the Philippines (Lutheran)

- The United Methodist Church (Methodist)

- United Church of Christ in the Philippines (Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Disciples, United Brethren, Methodist).

- Christ Living Epistle Ministries Inc. (Full Gospel/Pentecostal).

- Victory Christian Fellowship (Pentecostal)

- Cathedral of Praise (Pentecostal)

- Christ's Commission Fellowship

- Bread of Life Ministries International

- New Life Christian Center

- Pentecostal Missionary Church of Christ (4th Watch)

- Iglesia Evangelica Metodista en las Islas Filipinas

- Iglesia Evangelica Unida de Cristo

- United Evangelical Church of the Philippines

- Union Church Manila

- [Greenhills Christian Fellowship(Conservative Baptist)

- Word for the World Christian Fellowship

Filipino Catholic Church independent from Rome

- Philippine Independent Church more commonly known as the Iglesia Filipina Independiente or Aglipayans, arose from a Catholic nationalist movement at the turn of the century.It's the second biggest Christian denomination in the Philippines, after the Roman Catholic Church, which has parishes and churches around the Philippines and parishes around the United States, Europe, mostly in the UK and Sweden, and in Asia. The total membership counts vary from 3 to 7 million members. It is in full communion with the Philippine Episcopal Church, the rest of the Anglican Communion, and the Union of Utrecht.

- The Apostolic Catholic Church (ACC) is a catholic denomination founded in the 1980s in Hermosa, Bataan. It formally separated in the Roman Catholic Church in 1992 when Patriarch +Dr. John Florentine Teruel registered it as a Protestant and Independent Catholic denomination. Today, it has more than 5 million members worldwide. The largest international congregations are in Japan, USA and Canada.

Restorationist

Restorationism describes religious movements that follow what they understand to be a pristine, or original, form of Christianity. These movements and churches are considered as cults by the Christian Community as they significantly went off/contradicts from the historic Christian faith:

- The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormonism) - During the Spanish-American War in 1898, two men from Utah who were members of the United States artillery battery, and who were also set apart as missionaries by the Church before they left the United States, preached while stationed in the Philippines. Missionary work work picked up after World War II, and in 1961 the Church was officially registered in the Philippines.[15] In 1969, the Church had spread to eight major islands and had the highest number of baptisms of any area in the Church. A temple was built in 1984 which located in Quezon City and another one which is under construction is in Cebu City. The Manila Missionary Training Center was established in 1983. Membership in 1984 was 76,000 and 237,000 in 1990. Membership was 594,655 in 2007. In 2008, groundbreaking began on a new temple in Cebu.

- Jehovah's Witnesses - Missionaries of the Jehovah's Witnesses arrived in the Philippines during the American Occupation (1898–1945). They have been involved in several court controversies because of their stand on flag-saluting and blood transfusions. They are best known by their preaching in pairs from house to house. Currently there are more than 150,000 members in the Philippines as of the year 2006.

- The Kingdom of Jesus Christ, the Name Above Every Name - The Kingdom of Jesus Christ, the Name Above Every Name was founded by Pastor Apollo C. Quiboloy, claiming to be the appointed Son of God, on September 1, 1985. Quiboloy claims that salvation is through him and he is the residence of the Father. He also claims to restore the kingdom of God in the gentile settings.

- Members Church of God International - is a nontrinitarian religious organization colloquialy known through its Multi-awarded international television program, Ang Dating Daan (English for the "The Old Path"). This group is an offshoot of Nicholas Perez's Iglesia ng Diyos kay Kristo Hesus Haligi at Suhay ng Katotohanan (Church of God in Christ Jesus, Pillar and Support of the Truth). The church does not claim to be part of the restorationist movement but shows characteristics of such. They claim a different view about the personhood of God and of the divinity of Jesus Christ contrary to the historic Catholic beliefs. They also believe that the original church was apostatized.

- The Most Holy Church of God in Christ Jesus is a Philippine religious organization established in May, 1922 by Teofilo D. Ora. This church is also known in the country through its radio program Ang Kabanalbanalan which airs on several radio stations nationwide.[16][17]

- Seventh-day Adventist Church - The church founded by Ellen G. White which is best-known for its teaching that Saturday, the seventh day of the week, is the Sabbath, and that the second advent of Jesus Christ is imminent. As of 2007, there were 88,706 Adventist churches in the Philippines, with a membership of 571,653 and an annual membership growth rate of 5.6%.[18]

- Iglesia ni Cristo an indigenous[19] religious organization that originated from the Philippines[20][21][22][23] - The church was founded by Felix Manalo when he officially registered the church with the Philippine Government with him as executive minister on July 27, 1914 and because of this, most publications refer to him as the founder of the church. Felix Manalo claims that he is restoring the church of Christ that was lost for 2,000 years. The Iglesia ni Cristo is widely regarded as very influential due to their ability to deliver votes through block voting during elections. Their membership is not released in public but is estimated over 3 million.

- United Pentecostal Church International (Oneness)The church has originated from the United States of America as an offshoot of the pentecostal movements in the 1920s. The church is a proponent of the belief of modalism to describe God. They deny the Triune personhood of God.

- Jesus Christ To God be the Glory (Friends Again) founded by Luis Ruiz Santos in 1988. The church advocates "Oneness" belief about God.

- Jesus Miracle Crusade International Ministry founded by Wilde Almeda in the 1960s. They advocate "oneness" belief.

- Churches of Christ (Churches of Christ 33 AD/ the Stone-Campbellites) a restorationist movement distinctly believes in a set of steps/ways to attain salvation among of which is the requisite to be baptized in water.

- True Jesus Church a "oneness" movement that started in China.

- Jesus is Our Shield worldwide ministries (Oras ng Himala) founded by Renato D. Carillo, who claims to be the end-time apostle.

- Universal Church of the Kingdom of God (UCKG Help Center) founded by Edir Macedo in 1977 in Brazil. They claim that the Kingdom of God is down here and that it can offer a solution to every possible problem, depression, unemployment, family and financial problems.

Islam

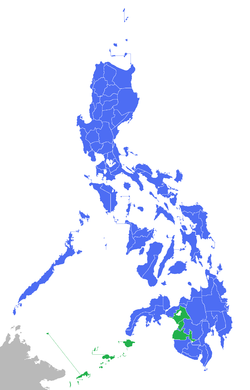

Islam reached the Philippines in the 14th century with the arrival of Malay and Javanese merchants and Arab merchants from Malaysia and Indonesia, although the spreading of Islam in the Philippines is due to the strength of Muslim India. India brought Islam to Southeast Asia, specifically Malaysia and Indonesia, and in turn the latter two brought Islam to the Philippines. Filipino Muslims make up about five percent of the population and are concentrated in the western portion of the island of Mindanao. The Bangsamoro or Muslim Nation, a term used to define the disparate ethnic groups that profess Islam in the Philippines as their religion, have been fighting the most protracted war of independence in world history. These include the Tausugs and the Maranaos. The Islamic separatist movement in the Philippines had been and is being waged for almost five centuries—against the Spanish, the Americans, the Japanese and the predominantly Christian Filipinos of today's independent republic. Filipino Muslims follow the Sunni tradition.

Sikhism and Hinduism

Hinduism and Vajrayana Buddhism has existed in the Philippines for centuries. A great deal of Philippine mythology is derived from Hindu mythology. Many Filipino customs have strong Buddhist influences. Hinduism arrived when the Hindu religion and culture arrived from India by southern Indians to Southeast Asia from the 4th centuries to the 14th century. The same case can also be found in Buddhism since early Buddhist did follow many of the Hindu cosmology and Hindus themselves considered Buddha to be an avatar of their god, Vishnu. The Srivijaya Empire and Majapahit Empire on what is now Malaysia and Indonesia, introduced Hinduism and Buddhism to the islands[24]. Statues of Hindu-Buddhist gods have been found in the Philippines.[25]

Today Hinduism is largely confined to the Indian Filipinos and the expatriate Indian community. Theravada and Vajrayana Buddhism, which are very close to Hinduism, are practiced by Tibetans, Sri Lankan, Burmese and Thai nationals. There are Hindu temples in Manila, as well as in the provinces. There are temples also for Sikhism, sometimes located near Hindu temples. The two Paco temples are well known, comprising a Hindu temple and a Sikh temple.

Atheism and agnosticism

Phil Zuckerman[26] estimated in 2007 that slightly less than 1% of the population of the Philippines were atheist.[27]

Discussions on atheism are active in academic institutions such as the University of the Philippines. One of the well known atheist organizations in UP is UPAC (University of the Philippines Atheist Circle).

Prominent atheists in the Philippines are quite few. Most notable is Mr. Ramon "Poch" Suzara of the Bertrand Russell Society, Philippines.

There were also atheists in Luneta Park, yet they never called themselves as "atheists”. Most Filipino non-believers are more comfortable to label themselves as agnostics, freethinkers, Humanist and rationalist rather than as atheists.

The advent of the Internet revolution in the 1990s was also a landmark in Philippine atheism. A lot of Filipino atheist went "out" and started posting their atheism on their personal blogs. There were also groups that came out like Radioactive atheist, a Yahoo atheist group created by Joebert Cuevas, Aleksi Gumela and Jose Juan "John" Paraiso in November 2002. Today there are a lot of atheist blogs and forum created by Filipinos. One of the first is Pinoy Atheist. Jose Juan “John” Paraiso created it on Feb 2005.

On February 2009, Filipino Freethinkers[28] was formed. The group, composed mostly of atheists, agnostics, and humanists, discuss daily through its online channels, with a combined membership of more than 200 members spread across their mailing list, forum, and social networking group. Aside from weekly meetings, they have held two open forums, with a combined attendance of over 100 members.

Statistics

The following statistics are from the CIA Factbook and the 2000 census:

- Christian: 92.5%[29]

- Muslim: 5%[29], 5.1%[10]

- Buddhist:3%[29], 2.1%[10]

- Other: 1.8%[29], 1.7%[10]

- None/DK: 0.5%[10]

See also

- Funeral practices and burial customs in the Philippines

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ronald E. Dolan, ed (1991). "Religion". Philippines: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. http://countrystudies.us/philippines/45.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-08

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 http://www.jewishtimesasia.org/manila/269-manila-communities/576-philippines-jewish-community

- ↑ http://www.chabad.ph/page.asp?pageID=D0C59F0E-E626-466C-804A-A7D138905F7E

- ↑ Schlossberger, E. Cauliflower and Ketchup.

- ↑ http://showbizandstyle.inquirer.net/lifestyle/lifestyle/view/20071224-108667/Unlocking_the_mysteries_of_the_heart_and_soul

- ↑ http://angilaw.wordpress.com/ang-ilaw/

- ↑ Hassall, Graham; Austria, Orwin (January 2000). "Mirza Hossein R. Touty: First Bahá'í known to have lived in the Philippines". Essays in Biography. Asia Pacific Bahá'í Studies. http://bahai-library.com/hassall_austria_hossein_touty. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

- ↑ Effendi, Shoghi (1944). God Passes By. Wilmette, Illinois, USA: Bahá'í Publishing Trust. ISBN 0-87743-020-9. http://reference.bahai.org/en/t/se/GPB/.

- ↑ Universal House of Justice (1986). In Memorium. XVIII. Bahá'í World Centre. Table of Contents and pp.513, 652–9. ISBN 0853982341. http://bahai-library.com/books/bw18/636-665.html

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 "Religious Demographic Profile — Philippines". The PEW forum on Religion & Public Life. Archived from the original on 2008-03-06. http://web.archive.org/web/20080306022227/http://pewforum.org/world-affairs/countries/?CountryID=163. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- ↑ "An Information Guide — Buddhism". buddhist-tourism.com. 2007. http://www.buddhist-tourism.com/countries/philippines/buddhism-in-philippines.html. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

- ↑ "History; Philippines". Sangha Pinoy. http://sanghapinoy.bravehost.com/directory.htm/. Retrieved 2008-05-13.

- ↑ "Orthodox Christians in Philippines". Orthodox Church in the Philippines. http://www.orthodox.org.ph/content/view/583/1/. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ Article Provided By Rev. Philemon Castro. "The Orthodox Church In The Philippines". Dimitris Papadias, Professor at the Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Hong Kong. http://www.cs.ust.hk/faculty/dimitris/metro/Phil_history.html. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ "New Temple Announcement Answers Members’ Prayers". News of the Church. Liahona. September 2006. http://lds.org/ldsorg/v/index.jsp?vgnextoid=f318118dd536c010VgnVCM1000004d82620aRCRD&locale=0&sourceId=f6416860ec8ad010VgnVCM1000004d82620a____&hideNav=1. Retrieved 2008-11-23

- ↑ "List of websites of other Religions in the Philippines". PinoySites.org. http://www.pinoysites.org/phil1197.htm. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ↑ "Christian Flags". flagspot.net. http://flagspot.net/flags/rel-mhcg.html. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ↑ Philippines, Adventist Atlas.

- ↑ "Iglesia ni Kristo". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/282267/Iglesia-ni-Kristo. Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- ↑ Sanders, Albert J., "An Appraisal of the Iglesia ni Cristo," in Studies in Philippine Church History, ed. Anderson, Gerald H. (Cornell University Press, 1969)

- ↑ Bevans, Stephen B.; Schroeder, Roger G.. Constants in Context: A Theology of Mission for Today (American Society of Missiology Series). Orbis Books. pp. 269. ISBN 1-57075-517-5.

- ↑ Carnes, Tony; Yang, Fenggang (2004). Asian American religions: the making and remaking of borders and boundaries. New York: New York University Press. pp. 352. ISBN 978-0-8147-1630-4.

- ↑ Kwiatkowski, Lynn M.. Struggling With Development: The Politics Of Hunger And Gender In The Philippines. Westview Press. pp. 286. ISBN 978-0-8133-3784-5.

- ↑ "History of Buddhism". Buddhism in the Philippines. http://sanghapinoy.bravehost.com/history.htm. Retrieved 2008-03-16

- ↑ Thakur, Upendra (1986). Some Aspects of Asia and Culture. Abhinav Publications.

- ↑ Phil Zuckerman is a professor of sociology at Pitzer College. His faculty profile states his areas of expertise as Sociology of Religion, Social Theory, and Deviance. He is a outspoken atheist and the author of, among other works, Zuckerman, Phil (2008). Society Without God: What the Least Religious Nations Can Tell Us About Contentment. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814797143. http://books.google.com/?id=mwmJ4FwuF2YC.

- ↑ Zuckerman, Phil (2007). "Atheism : Contemporary Numbers and patterns". In Martin, Michael. The Cambridge companion to atheism. Cambridge University Press. p. http://books.google.com/books?id=tAeFipOVx4MC&pg=PA61. ISBN 9780521842709. http://books.google.com/books?id=tAeFipOVx4MC&pg=PA47.

- ↑ "Filipino Freethinkers Official Website". http://filipinofreethinkers.org. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 29.6 29.7 29.8 "Philippines - People". CIA Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rp.html. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||